Mums for Lungs was set up by a group of parents in South London in 2017 campaigning to solve the problem of London’s toxic air, writes Celeste Hicks.

When I was pregnant with my first child, I had a breath test at a midwife appointment. She told me I had high levels of carbon monoxide in my body. I was shocked. She asked if I smoked, which I didn’t, or whether I had a faulty boiler. Eventually, we concluded it must have been pollution from road traffic.

I had been cycling to work in central London for years. I was aware of the annoyance of sitting behind lorries with their engines idling at traffic lights, but I had never thought about what that was doing to my body. If I had been a smoker, I could have given up. But what could I possibly do to stop fumes from traffic getting into my body and harming my unborn child?

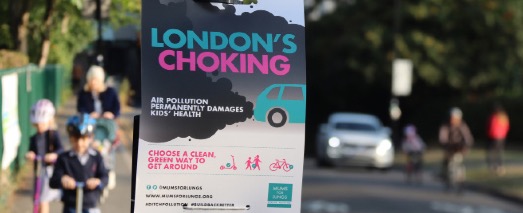

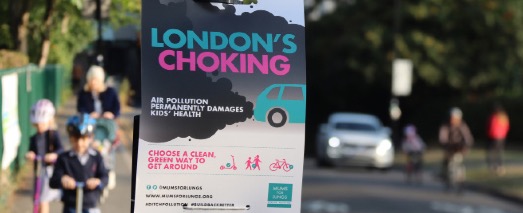

I didn’t know anyone else who was really worried about air pollution until I saw a poster in a South London park advertising Mums for Lungs. I went along to an early meeting in 2017 and met other mums who had realised the scale of the public health crisis caused by air pollution as they had become parents.

In the early days, we drank lots of tea in each other’s houses, educating ourselves and looking for ways to take action. From a handful of members, we now have several groups across London and include dads and grandparents among our volunteers, who meet regularly with our three part-time staff members to discuss current developments, successes, challenges, and new ideas to fight for clean air.

We are united in our determination to achieve clean air for everyone, particularly children and babies. We have a vision of a future where road space is prioritised more towards the needs of pedestrians. It’s not simply about pollution. We know that globally road traffic collisions are one of the biggest killers of children. We have been working for four years to develop initiatives to promote clean air and a safe journey to school. Over 350 School Streets have been established in London in the last three years, where roads are closed to traffic at drop off and pick up time. We’ve lobbied politicians, held car-free street parties, and created street art to raise awareness about the worst air pollution hotspots.

Children are particularly affected by air pollution. They have smaller lungs, which means they breathe faster, and their bodies are growing, changing, and developing. When they stand by the side of busy roads, their smaller size means they are closer to the source of the emissions from vehicle tailpipes.

The science is clear: air pollution they breathe in now can affect them for the rest of their lives. A study by King’s College London showed that children who had been exposed to air pollution had lungs up to 5% smaller than average. We know air pollution has been associated with lung disease, heart disease, dementia, teenage psychotic episodes, and even miscarriage. In 2020, a coroner concluded that air pollution was a contributing factor in the death of a nine-year-old London girl, Ella Kissi-Debrah after she suffered multiple serious asthma attacks.

There are two main pollutants of concern: nitrogen dioxide (NO2), which comes from burning diesel, and particulate matter (tiny particles of dust, soot, plastic and metal), which comes from a variety of sources including tyre wear and tear and domestic wood burning. Mums for Lungs is campaigning for a switch from these polluting fuels. Switching from diesel to electric will likely see a significant reduction in NO2 emissions, however, there will still be emissions of PM from electric vehicles, partly because they are heavier.

‘Dieselgate’ showed that car manufacturers knew diesel cars were causing much more pollution than the public understood, and yet several years later we are still struggling to clean up our fleets. Mums for Lungs would like to see the logistics industry moving towards the rollout of EVs as well as changes such as grouping deliveries or using cargo bikes for shorter distances. We are delighted to work together to enact some of the changes we need for all our future health.

Originally posted in the FVI magazine